January, 2016

Microsoft is making this Specification available under the Open Web Foundation Final Specification Agreement Version 1.0 (“OWF 1.0”) as of October 1, 2012. The OWF 1.0 is available at here.

TypeScript is a trademark of Microsoft Corporation.

JavaScript applications such as web e-mail, maps, document editing, and collaboration tools are becoming an increasingly important part of the everyday computing. We designed TypeScript to meet the needs of the JavaScript programming teams that build and maintain large JavaScript programs. TypeScript helps programming teams to define interfaces between software components and to gain insight into the behavior of existing JavaScript libraries. TypeScript also enables teams to reduce naming conflicts by organizing their code into dynamically-loadable modules. TypeScript’s optional type system enables JavaScript programmers to use highly-productive development tools and practices: static checking, symbol-based navigation, statement completion, and code re-factoring.

TypeScript is a syntactic sugar for JavaScript. TypeScript syntax is a superset of ECMAScript 2015 (ES2015) syntax. Every JavaScript program is also a TypeScript program. The TypeScript compiler performs only file-local transformations on TypeScript programs and does not re-order variables declared in TypeScript. This leads to JavaScript output that closely matches the TypeScript input. TypeScript does not transform variable names, making tractable the direct debugging of emitted JavaScript. TypeScript optionally provides source maps, enabling source-level debugging. TypeScript tools typically emit JavaScript upon file save, preserving the test, edit, refresh cycle commonly used in JavaScript development.

TypeScript syntax includes all features of ECMAScript 2015, including classes and modules, and provides the ability to translate these features into ECMAScript 3 or 5 compliant code.

Classes enable programmers to express common object-oriented patterns in a standard way, making features like inheritance more readable and interoperable. Modules enable programmers to organize their code into components while avoiding naming conflicts. The TypeScript compiler provides module code generation options that support either static or dynamic loading of module contents.

TypeScript also provides to JavaScript programmers a system of optional type annotations. These type annotations are like the JSDoc comments found in the Closure system, but in TypeScript they are integrated directly into the language syntax. This integration makes the code more readable and reduces the maintenance cost of synchronizing type annotations with their corresponding variables.

The TypeScript type system enables programmers to express limits on the capabilities of JavaScript objects, and to use tools that enforce these limits. To minimize the number of annotations needed for tools to become useful, the TypeScript type system makes extensive use of type inference. For example, from the following statement, TypeScript will infer that the variable ‘i’ has the type number.

var i = 0;

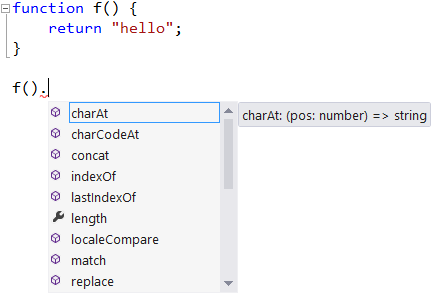

TypeScript will infer from the following function definition that the function f has return type string.

function f() {

return "hello";

}

To benefit from this inference, a programmer can use the TypeScript language service. For example, a code editor can incorporate the TypeScript language service and use the service to find the members of a string object as in the following screen shot.

In this example, the programmer benefits from type inference without providing type annotations. Some beneficial tools, however, do require the programmer to provide type annotations. In TypeScript, we can express a parameter requirement as in the following code fragment.

function f(s: string) {

return s;

}

f({}); // Error

f("hello"); // Ok

This optional type annotation on the parameter ’s’ lets the TypeScript type checker know that the programmer expects parameter ’s’ to be of type ‘string’. Within the body of function ‘f’, tools can assume ’s’ is of type ‘string’ and provide operator type checking and member completion consistent with this assumption. Tools can also signal an error on the first call to ‘f’, because ‘f’ expects a string, not an object, as its parameter. For the function ‘f’, the TypeScript compiler will emit the following JavaScript code:

function f(s) {

return s;

}

In the JavaScript output, all type annotations have been erased. In general, TypeScript erases all type information before emiting JavaScript.

An ambient declaration introduces a variable into a TypeScript scope, but has zero impact on the emitted JavaScript program. Programmers can use ambient declarations to tell the TypeScript compiler that some other component will supply a variable. For example, by default the TypeScript compiler will print an error for uses of undefined variables. To add some of the common variables defined by browsers, a TypeScript programmer can use ambient declarations. The following example declares the ‘document’ object supplied by browsers. Because the declaration does not specify a type, the type ‘any’ is inferred. The type ‘any’ means that a tool can assume nothing about the shape or behavior of the document object. Some of the examples below will illustrate how programmers can use types to further characterize the expected behavior of an object.

declare var document;

document.title = "Hello"; // Ok because document has been declared

In the case of ‘document’, the TypeScript compiler automatically supplies a declaration, because TypeScript by default includes a file ’lib.d.ts’ that provides interface declarations for the built-in JavaScript library as well as the Document Object Model.

The TypeScript compiler does not include by default an interface for jQuery, so to use jQuery, a programmer could supply a declaration such as:

declare var $;

Section 1.3 provides a more extensive example of how a programmer can add type information for jQuery and other libraries.

Function expressions are a powerful feature of JavaScript. They enable function definitions to create closures: functions that capture information from the lexical scope surrounding the function’s definition. Closures are currently JavaScript’s only way of enforcing data encapsulation. By capturing and using environment variables, a closure can retain information that cannot be accessed from outside the closure. JavaScript programmers often use closures to express event handlers and other asynchronous callbacks, in which another software component, such as the DOM, will call back into JavaScript through a handler function.

TypeScript function types make it possible for programmers to express the expected signature of a function. A function signature is a sequence of parameter types plus a return type. The following example uses function types to express the callback signature requirements of an asynchronous voting mechanism.

function vote(candidate: string, callback: (result: string) => any) {

// ...

}

vote("BigPig",

function(result: string) {

if (result === "BigPig") {

// ...

}

}

);

In this example, the second parameter to ‘vote’ has the function type

(result: string) => any

which means the second parameter is a function returning type ‘any’ that has a single parameter of type ‘string’ named ‘result’.

Section 3.9.2 provides additional information about function types.

TypeScript programmers use object types to declare their expectations of object behavior. The following code uses an object type literal to specify the return type of the ‘MakePoint’ function.

var MakePoint: () => {

x: number; y: number;

};

Programmers can give names to object types; we call named object types interfaces. For example, in the following code, an interface declares one required field (name) and one optional field (favoriteColor).

interface Friend {

name: string;

favoriteColor?: string;

}

function add(friend: Friend) {

var name = friend.name;

}

add({ name: "Fred" }); // Ok

add({ favoriteColor: "blue" }); // Error, name required

add({ name: "Jill", favoriteColor: "green" }); // Ok

TypeScript object types model the diversity of behaviors that a JavaScript object can exhibit. For example, the jQuery library defines an object, ‘$’, that has methods, such as ‘get’ (which sends an Ajax message), and fields, such as ‘browser’ (which gives browser vendor information). However, jQuery clients can also call ‘$’ as a function. The behavior of this function depends on the type of parameters passed to the function.

The following code fragment captures a small subset of jQuery behavior, just enough to use jQuery in a simple way.

interface JQuery {

text(content: string);

}

interface JQueryStatic {

get(url: string, callback: (data: string) => any);

(query: string): JQuery;

}

declare var $: JQueryStatic;

$.get("http://mysite.org/divContent",

function (data: string) {

$("div").text(data);

}

);

The ‘JQueryStatic’ interface references another interface: ‘JQuery’. This interface represents a collection of one or more DOM elements. The jQuery library can perform many operations on such a collection, but in this example the jQuery client only needs to know that it can set the text content of each jQuery element in a collection by passing a string to the ’text’ method. The ‘JQueryStatic’ interface also contains a method, ‘get’, that performs an Ajax get operation on the provided URL and arranges to invoke the provided callback upon receipt of a response.

Finally, the ‘JQueryStatic’ interface contains a bare function signature

(query: string): JQuery;

The bare signature indicates that instances of the interface are callable. This example illustrates that TypeScript function types are just special cases of TypeScript object types. Specifically, function types are object types that contain one or more call signatures. For this reason we can write any function type as an object type literal. The following example uses both forms to describe the same type.

var f: { (): string; };

var sameType: () => string = f; // Ok

var nope: () => number = sameType; // Error: type mismatch

We mentioned above that the ‘$’ function behaves differently depending on the type of its parameter. So far, our jQuery typing only captures one of these behaviors: return an object of type ‘JQuery’ when passed a string. To specify multiple behaviors, TypeScript supports overloading of function signatures in object types. For example, we can add an additional call signature to the ‘JQueryStatic’ interface.

(ready: () => any): any;

This signature denotes that a function may be passed as the parameter of the ‘$’ function. When a function is passed to ‘$’, the jQuery library will invoke that function when a DOM document is ready. Because TypeScript supports overloading, tools can use TypeScript to show all available function signatures with their documentation tips and to give the correct documentation once a function has been called with a particular signature.

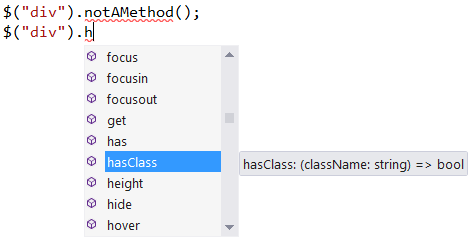

A typical client would not need to add any additional typing but could just use a community-supplied typing to discover (through statement completion with documentation tips) and verify (through static checking) correct use of the library, as in the following screen shot.

Section 3.3 provides additional information about object types.

Object types are compared structurally. For example, in the code fragment below, class ‘CPoint’ matches interface ‘Point’ because ‘CPoint’ has all of the required members of ‘Point’. A class may optionally declare that it implements an interface, so that the compiler will check the declaration for structural compatibility. The example also illustrates that an object type can match the type inferred from an object literal, as long as the object literal supplies all of the required members.

interface Point {

x: number;

y: number;

}

function getX(p: Point) {

return p.x;

}

class CPoint {

x: number;

y: number;

constructor(x: number, y: number) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

}

getX(new CPoint(0, 0)); // Ok, fields match

getX({ x: 0, y: 0, color: "red" }); // Extra fields Ok

getX({ x: 0 }); // Error: supplied parameter does not match

See section 3.11 for more information about type comparisons.

Ordinarily, TypeScript type inference proceeds “bottom-up”: from the leaves of an expression tree to its root. In the following example, TypeScript infers ’number’ as the return type of the function ‘mul’ by flowing type information bottom up in the return expression.

function mul(a: number, b: number) {

return a * b;

}

For variables and parameters without a type annotation or a default value, TypeScript infers type ‘any’, ensuring that compilers do not need non-local information about a function’s call sites to infer the function’s return type. Generally, this bottom-up approach provides programmers with a clear intuition about the flow of type information.

However, in some limited contexts, inference proceeds “top-down” from the context of an expression. Where this happens, it is called contextual typing. Contextual typing helps tools provide excellent information when a programmer is using a type but may not know all of the details of the type. For example, in the jQuery example, above, the programmer supplies a function expression as the second parameter to the ‘get’ method. During typing of that expression, tools can assume that the type of the function expression is as given in the ‘get’ signature and can provide a template that includes parameter names and types.

$.get("http://mysite.org/divContent",

function (data) {

$("div").text(data); // TypeScript infers data is a string

}

);

Contextual typing is also useful for writing out object literals. As the programmer types the object literal, the contextual type provides information that enables tools to provide completion for object member names.

Section 4.23 provides additional information about contextually typed expressions.

JavaScript practice has two very common design patterns: the module pattern and the class pattern. Roughly speaking, the module pattern uses closures to hide names and to encapsulate private data, while the class pattern uses prototype chains to implement many variations on object-oriented inheritance mechanisms. Libraries such as ‘prototype.js’ are typical of this practice. TypeScript’s namespaces are a formalization of the module pattern. (The term “module pattern” is somewhat unfortunate now that ECMAScript 2015 formally supports modules in a manner different from what the module pattern prescribes. For this reason, TypeScript uses the term “namespace” for its formalization of the module pattern.)

This section and the namespace section below will show how TypeScript emits consistent, idiomatic JavaScript when emitting ECMAScript 3 or 5 compliant code for classes and namespaces. The goal of TypeScript’s translation is to emit exactly what a programmer would type when implementing a class or namespace unaided by a tool. This section will also describe how TypeScript infers a type for each class declaration. We’ll start with a simple BankAccount class.

class BankAccount {

balance = 0;

deposit(credit: number) {

this.balance += credit;

return this.balance;

}

}

This class generates the following JavaScript code.

var BankAccount = (function () {

function BankAccount() {

this.balance = 0;

}

BankAccount.prototype.deposit = function(credit) {

this.balance += credit;

return this.balance;

};

return BankAccount;

})();

This TypeScript class declaration creates a variable named ‘BankAccount’ whose value is the constructor function for ‘BankAccount’ instances. This declaration also creates an instance type of the same name. If we were to write this type as an interface it would look like the following.

interface BankAccount {

balance: number;

deposit(credit: number): number;

}

If we were to write out the function type declaration for the ‘BankAccount’ constructor variable, it would have the following form.

var BankAccount: new() => BankAccount;

The function signature is prefixed with the keyword ’new’ indicating that the ‘BankAccount’ function must be called as a constructor. It is possible for a function’s type to have both call and constructor signatures. For example, the type of the built-in JavaScript Date object includes both kinds of signatures.

If we want to start our bank account with an initial balance, we can add to the ‘BankAccount’ class a constructor declaration.

class BankAccount {

balance: number;

constructor(initially: number) {

this.balance = initially;

}

deposit(credit: number) {

this.balance += credit;

return this.balance;

}

}

This version of the ‘BankAccount’ class requires us to introduce a constructor parameter and then assign it to the ‘balance’ field. To simplify this common case, TypeScript accepts the following shorthand syntax.

class BankAccount {

constructor(public balance: number) {

}

deposit(credit: number) {

this.balance += credit;

return this.balance;

}

}

The ‘public’ keyword denotes that the constructor parameter is to be retained as a field. Public is the default accessibility for class members, but a programmer can also specify private or protected accessibility for a class member. Accessibility is a design-time construct; it is enforced during static type checking but does not imply any runtime enforcement.

TypeScript classes also support inheritance, as in the following example.* *

class CheckingAccount extends BankAccount {

constructor(balance: number) {

super(balance);

}

writeCheck(debit: number) {

this.balance -= debit;

}

}

In this example, the class ‘CheckingAccount’ derives from class ‘BankAccount’. The constructor for ‘CheckingAccount’ calls the constructor for class ‘BankAccount’ using the ‘super’ keyword. In the emitted JavaScript code, the prototype of ‘CheckingAccount’ will chain to the prototype of ‘BankAccount’.

TypeScript classes may also specify static members. Static class members become properties of the class constructor.

Section 8 provides additional information about classes.

TypeScript enables programmers to summarize a set of numeric constants as an enum type. The example below creates an enum type to represent operators in a calculator application.

const enum Operator {

ADD,

DIV,

MUL,

SUB

}

function compute(op: Operator, a: number, b: number) {

console.log("the operator is" + Operator[op]);

// ...

}

In this example, the compute function logs the operator ‘op’ using a feature of enum types: reverse mapping from the enum value (‘op’) to the string corresponding to that value. For example, the declaration of ‘Operator’ automatically assigns integers, starting from zero, to the listed enum members. Section 9 describes how programmers can also explicitly assign integers to enum members, and can use any string to name an enum member.

When enums are declared with the const modifier, the TypeScript compiler will emit for an enum member a JavaScript constant corresponding to that member’s assigned value (annotated with a comment). This improves performance on many JavaScript engines.

For example, the ‘compute’ function could contain a switch statement like the following.

switch (op) {

case Operator.ADD:

// execute add

break;

case Operator.DIV:

// execute div

break;

// ...

}

For this switch statement, the compiler will generate the following code.

switch (op) {

case 0 /* Operator.ADD */:

// execute add

break;

case 1 /* Operator.DIV */:

// execute div

break;

// ...

}

JavaScript implementations can use these explicit constants to generate efficient code for this switch statement, for example by building a jump table indexed by case value.

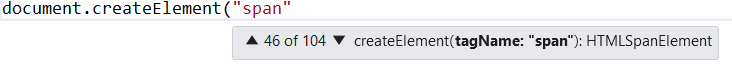

An important goal of TypeScript is to provide accurate and straightforward types for existing JavaScript programming patterns. To that end, TypeScript includes generic types, discussed in the next section, and overloading on string parameters, the topic of this section.

JavaScript programming interfaces often include functions whose behavior is discriminated by a string constant passed to the function. The Document Object Model makes heavy use of this pattern. For example, the following screen shot shows that the ‘createElement’ method of the ‘document’ object has multiple signatures, some of which identify the types returned when specific strings are passed into the method.

The following code fragment uses this feature. Because the ‘span’ variable is inferred to have the type ‘HTMLSpanElement’, the code can reference without static error the ‘isMultiline’ property of ‘span’.

var span = document.createElement("span");

span.isMultiLine = false; // OK: HTMLSpanElement has isMultiline property

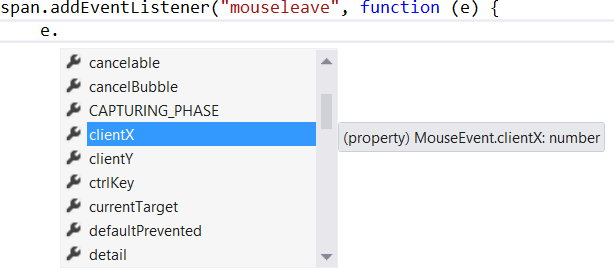

In the following screen shot, a programming tool combines information from overloading on string parameters with contextual typing to infer that the type of the variable ’e’ is ‘MouseEvent’ and that therefore ’e’ has a ‘clientX’ property.

Section 3.9.2.4 provides details on how to use string literals in function signatures.

Like overloading on string parameters, generic types make it easier for TypeScript to accurately capture the behavior of JavaScript libraries. Because they enable type information to flow from client code, through library code, and back into client code, generic types may do more than any other TypeScript feature to support detailed API descriptions.

To illustrate this, let’s take a look at part of the TypeScript interface for the built-in JavaScript array type. You can find this interface in the ’lib.d.ts’ file that accompanies a TypeScript distribution.

interface Array<T> {

reverse(): T[];

sort(compareFn?: (a: T, b: T) => number): T[];

// ...

}

Interface definitions, like the one above, can have one or more type parameters. In this case the ‘Array’ interface has a single parameter, ‘T’, that defines the element type for the array. The ‘reverse’ method returns an array with the same element type. The sort method takes an optional parameter, ‘compareFn’, whose type is a function that takes two parameters of type ‘T’ and returns a number. Finally, sort returns an array with element type ‘T’.

Functions can also have generic parameters. For example, the array interface contains a ‘map’ method, defined as follows:

map<U>(func: (value: T, index: number, array: T[]) => U, thisArg?: any): U[];

The map method, invoked on an array ‘a’ with element type ‘T’, will apply function ‘func’ to each element of ‘a’, returning a value of type ‘U’.

The TypeScript compiler can often infer generic method parameters, making it unnecessary for the programmer to explicitly provide them. In the following example, the compiler infers that parameter ‘U’ of the map method has type ‘string’, because the function passed to map returns a string.

function numberToString(a: number[]) {

var stringArray = a.map(v => v.toString());

return stringArray;

}

The compiler infers in this example that the ’numberToString’ function returns an array of strings.

In TypeScript, classes can also have type parameters. The following code declares a class that implements a linked list of items of type ‘T’. This code illustrates how programmers can constrain type parameters to extend a specific type. In this case, the items on the list must extend the type ‘NamedItem’. This enables the programmer to implement the ’log’ function, which logs the name of the item.

interface NamedItem {

name: string;

}

class List<T extends NamedItem> {

next: List<T> = null;

constructor(public item: T) {

}

insertAfter(item: T) {

var temp = this.next;

this.next = new List(item);

this.next.next = temp;

}

log() {

console.log(this.item.name);

}

// ...

}

Section 3.7 provides further information about generic types.

Classes and interfaces support large-scale JavaScript development by providing a mechanism for describing how to use a software component that can be separated from that component’s implementation. TypeScript enforces encapsulation of implementation in classes at design time (by restricting use of private and protected members), but cannot enforce encapsulation at runtime because all object properties are accessible at runtime. Future versions of JavaScript may provide private names which would enable runtime enforcement of private and protected members.

In JavaScript, a very common way to enforce encapsulation at runtime is to use the module pattern: encapsulate private fields and methods using closure variables. The module pattern is a natural way to provide organizational structure and dynamic loading options by drawing a boundary around a software component. The module pattern can also provide the ability to introduce namespaces, avoiding use of the global namespace for most software components.

The following example illustrates the JavaScript module pattern.

(function(exports) {

var key = generateSecretKey();

function sendMessage(message) {

sendSecureMessage(message, key);

}

exports.sendMessage = sendMessage;

})(MessageModule);

This example illustrates the two essential elements of the module pattern: a module closure and a module object. The module closure is a function that encapsulates the module’s implementation, in this case the variable ‘key’ and the function ‘sendMessage’. The module object contains the exported variables and functions of the module. Simple modules may create and return the module object. The module above takes the module object as a parameter, ’exports’, and adds the ‘sendMessage’ property to the module object. This augmentation approach simplifies dynamic loading of modules and also supports separation of module code into multiple files.

The example assumes that an outer lexical scope defines the functions ‘generateSecretKey’ and ‘sendSecureMessage’; it also assumes that the outer scope has assigned the module object to the variable ‘MessageModule’.

TypeScript namespaces provide a mechanism for succinctly expressing the module pattern. In TypeScript, programmers can combine the module pattern with the class pattern by nesting namespaces and classes within an outer namespace.

The following example shows the definition and use of a simple namespace.

namespace M {

var s = "hello";

export function f() {

return s;

}

}

M.f();

M.s; // Error, s is not exported

In this example, variable ’s’ is a private feature of the namespace, but function ‘f’ is exported from the namespace and accessible to code outside of the namespace. If we were to describe the effect of namespace ‘M’ in terms of interfaces and variables, we would write

interface M {

f(): string;

}

var M: M;

The interface ‘M’ summarizes the externally visible behavior of namespace ‘M’. In this example, we can use the same name for the interface as for the initialized variable because in TypeScript type names and variable names do not conflict: each lexical scope contains a variable declaration space and type declaration space (see section 2.3 for more details).

The TypeScript compiler emits the following JavaScript code for the namespace:

var M;

(function(M) {

var s = "hello";

function f() {

return s;

}

M.f = f;

})(M || (M = {}));

In this case, the compiler assumes that the namespace object resides in global variable ‘M’, which may or may not have been initialized to the desired namespace object.

TypeScript also supports ECMAScript 2015 modules, which are files that contain top-level export and import directives. For this type of module the TypeScript compiler can emit both ECMAScript 2015 compliant code and down-level ECMAScript 3 or 5 compliant code for a variety of module loading systems, including CommonJS, Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD), and Universal Module Definition (UMD).

The remainder of this document is the formal specification of the TypeScript programming language and is intended to be read as an adjunct to the ECMAScript 2015 Language Specification (specifically, the ECMA-262 Standard, 6th Edition). This document describes the syntactic grammar added by TypeScript along with the compile-time processing and type checking performed by the TypeScript compiler, but it only minimally discusses the run-time behavior of programs since that is covered by the ECMAScript specification.

The syntactic grammar added by TypeScript language is specified throughout this document using the existing conventions and production names of the ECMAScript grammar. In places where TypeScript augments an existing grammar production it is so noted. For example:

Declaration: ( Modified )

…

InterfaceDeclaration

TypeAliasDeclaration

EnumDeclaration

The ‘( Modified )’ annotation indicates that an existing grammar production is being replaced, and the ‘…’ references the contents of the original grammar production.

Similar to the ECMAScript grammar, if the phrase “[no LineTerminator here]” appears in the right-hand side of a production of the syntactic grammar, it indicates that the production is not a match if a LineTerminator occurs in the input stream at the indicated position.

A core purpose of the TypeScript compiler is to track the named entities in a program and validate that they are used according to their designated meaning. Names in TypeScript can be written in several ways, depending on context. Specifically, a name can be written as

Most commonly, names are written to conform with the Identifier production, which is any IdentifierName that isn’t a reserved word.

The following keywords are reserved and cannot be used as an Identifier:

break case catch class

const continue debugger default

delete do else enum

export extends false finally

for function if import

in instanceof new null

return super switch this

throw true try typeof

var void while with

The following keywords cannot be used as identifiers in strict mode code, but are otherwise not restricted:

implements interface let package

private protected public static

yield

The following keywords cannot be used as user defined type names, but are otherwise not restricted:

any boolean number string

symbol

The following keywords have special meaning in certain contexts, but are valid identifiers:

abstract as async await

constructor declare from get

is module namespace of

require set type

The PropertyName production from the ECMAScript grammar is reproduced below:

PropertyName:

LiteralPropertyName

ComputedPropertyName

LiteralPropertyName:

IdentifierName

StringLiteral

NumericLiteral

ComputedPropertyName:

[ AssignmentExpression ]

A property name can be any identifier (including a reserved word), a string literal, a numeric literal, or a computed property name. String literals may be used to give properties names that are not valid identifiers, such as names containing blanks. Numeric literal property names are equivalent to string literal property names with the string representation of the numeric literal, as defined in the ECMAScript specification.

ECMAScript 2015 permits object literals and classes to declare members with computed property names. A computed property name specifies an expression that computes the actual property name at run-time. Because the final property name isn’t known at compile-time, TypeScript can only perform limited checks for entities declared with computed property names. However, a subset of computed property names known as well-known symbols can be used anywhere a PropertyName is expected, including property names within types. A computed property name is a well-known symbol if it is of the form

[ Symbol . xxx ]

In a well-known symbol, the identifier to the right of the dot must denote a property of the primitive type symbol in the type of the global variable ‘Symbol’, or otherwise an error occurs.

In a PropertyName that specifies a ComputedPropertyName, the computed property name is required to denote a well-known symbol unless the property name occurs in a property assignment of an object literal (4.5) or a property member declaration in a non-ambient class (8.4).

Below is an example of an interface that declares a property with a well-known symbol name:

interface Iterable<T> {

[Symbol.iterator](): Iterator<T>;

}

TODO: Update to reflect treatment of computed property names with literal expressions.

Declarations introduce names in their associated declaration spaces. A name must be unique in its declaration space and can denote a value, a type, or a namespace, or some combination thereof. Effectively, a single name can have as many as three distinct meanings. For example:

var X: string; // Value named X

type X = number; // Type named X

namespace X { // Namespace named X

type Y = string;

}

A name that denotes a value has an associated type (section 3) and can be referenced in expressions (section 4.3). A name that denotes a type can be used by itself in a type reference or on the right hand side of a dot in a type reference (3.8.2). A name that denotes a namespace can be used one the left hand side of a dot in a type reference.

When a name with multiple meanings is referenced, the context in which the reference occurs determines the meaning. For example:

var n: X; // X references type

var s: X.Y = X; // First X references namespace, second X references value

In the first line, X references the type X because it occurs in a type position. In the second line, the first X references the namespace X because it occurs before a dot in a type name, and the second X references the variable X because it occurs in an expression.

Declarations introduce the following meanings for the name they declare:

Below are some examples of declarations that introduce multiple meanings for a name:

class C { // Value and type named C

x: string;

}

namespace N { // Value and namespace named N

export var x: string;

}

Declaration spaces exist as follows:

Top-level declarations in a source file with no top-level import or export declarations belong to the global namespace. Top-level declarations in a source file with one or more top-level import or export declarations belong to the module represented by that source file.

The container of an entity is defined as follows:

The root container of an entity is defined as follows:

Intuitively, the root container of an entity is the outermost module or namespace body from within which the entity is reachable.

Interfaces, enums, and namespaces are “open ended,” meaning that interface, enum, and namespace declarations with the same qualified name relative to a common root are automatically merged. For further details, see sections 7.2, 9.3, and 10.5.

Instance and static members in a class are in separate declaration spaces. Thus the following is permitted:

class C {

x: number; // Instance member

static x: string; // Static member

}

The scope of a name is the region of program text within which it is possible to refer to the entity declared by that name without qualification of the name. The scope of a name depends on the context in which the name is declared. The contexts are listed below in order from outermost to innermost:

Scopes may overlap, for example through nesting of namespaces and functions. When the scopes of two names overlap, the name with the innermost declaration takes precedence and access to the outer name is either not possible or only possible by qualification.

When an identifier is resolved as a PrimaryExpression (section 4.3), only names in scope with a value meaning are considered and other names are ignored.

When an identifier is resolved as a TypeName (section 3.8.2), only names in scope with a type meaning are considered and other names are ignored.

When an identifier is resolved as a NamespaceName (section 3.8.2), only names in scope with a namespace meaning are considered and other names are ignored.

TODO: Include specific rules for alias resolution.

Note that class and interface members are never directly in scope—they can only be accessed by applying the dot (’.’) operator to a class or interface instance. This even includes members of the current instance in a constructor or member function, which are accessed by applying the dot operator to this.

As the rules above imply, locally declared entities in a namespace are closer in scope than exported entities declared in other namespace declarations for the same namespace. For example:

var x = 1;

namespace M {

export var x = 2;

console.log(x); // 2

}

namespace M {

console.log(x); // 2

}

namespace M {

var x = 3;

console.log(x); // 3

}

TypeScript adds optional static types to JavaScript. Types are used to place static constraints on program entities such as functions, variables, and properties so that compilers and development tools can offer better verification and assistance during software development. TypeScript’s static compile-time type system closely models the dynamic run-time type system of JavaScript, allowing programmers to accurately express the type relationships that are expected to exist when their programs run and have those assumptions pre-validated by the TypeScript compiler. TypeScript’s type analysis occurs entirely at compile-time and adds no run-time overhead to program execution.

All types in TypeScript are subtypes of a single top type called the Any type. The any keyword references this type. The Any type is the one type that can represent any JavaScript value with no constraints. All other types are categorized as primitive types, object types, union types, intersection types, or type parameters. These types introduce various static constraints on their values.

The primitive types are the Number, Boolean, String, Symbol, Void, Null, and Undefined types along with user defined enum types. The number, boolean, string, symbol, and void keywords reference the Number, Boolean, String, Symbol, and Void primitive types respectively. The Void type exists purely to indicate the absence of a value, such as in a function with no return value. It is not possible to explicitly reference the Null and Undefined types—only values of those types can be referenced, using the null and undefined literals.

The object types are all class, interface, array, tuple, function, and constructor types. Class and interface types are introduced through class and interface declarations and are referenced by the name given to them in their declarations. Class and interface types may be generic types which have one or more type parameters.

Union types represent values that have one of multiple types, and intersection types represent values that simultaneously have more than one type.

Declarations of classes, properties, functions, variables and other language entities associate types with those entities. The mechanism by which a type is formed and associated with a language entity depends on the particular kind of entity. For example, a namespace declaration associates the namespace with an anonymous type containing a set of properties corresponding to the exported variables and functions in the namespace, and a function declaration associates the function with an anonymous type containing a call signature corresponding to the parameters and return type of the function. Types can be associated with variables through explicit type annotations, such as

var x: number;

or through implicit type inference, as in

var x = 1;

which infers the type of ‘x’ to be the Number primitive type because that is the type of the value used to initialize ‘x’.

The Any type is used to represent any JavaScript value. A value of the Any type supports the same operations as a value in JavaScript and minimal static type checking is performed for operations on Any values. Specifically, properties of any name can be accessed through an Any value and Any values can be called as functions or constructors with any argument list.

The any keyword references the Any type. In general, in places where a type is not explicitly provided and TypeScript cannot infer one, the Any type is assumed.

The Any type is a supertype of all types, and is assignable to and from all types.

Some examples:

var x: any; // Explicitly typed

var y; // Same as y: any

var z: { a; b; }; // Same as z: { a: any; b: any; }

function f(x) { // Same as f(x: any): void

console.log(x);

}

The primitive types are the Number, Boolean, String, Symbol, Void, Null, and Undefined types and all user defined enum types.

The Number primitive type corresponds to the similarly named JavaScript primitive type and represents double-precision 64-bit format IEEE 754 floating point values.

The number keyword references the Number primitive type and numeric literals may be used to write values of the Number primitive type.

For purposes of determining type relationships (section 3.11) and accessing properties (section 4.13), the Number primitive type behaves as an object type with the same properties as the global interface type ‘Number’.

Some examples:

var x: number; // Explicitly typed

var y = 0; // Same as y: number = 0

var z = 123.456; // Same as z: number = 123.456

var s = z.toFixed(2); // Property of Number interface

The Boolean primitive type corresponds to the similarly named JavaScript primitive type and represents logical values that are either true or false.

The boolean keyword references the Boolean primitive type and the true and false literals reference the two Boolean truth values.

For purposes of determining type relationships (section 3.11) and accessing properties (section 4.13), the Boolean primitive type behaves as an object type with the same properties as the global interface type ‘Boolean’.

Some examples:

var b: boolean; // Explicitly typed

var yes = true; // Same as yes: boolean = true

var no = false; // Same as no: boolean = false

The String primitive type corresponds to the similarly named JavaScript primitive type and represents sequences of characters stored as Unicode UTF-16 code units.

The string keyword references the String primitive type and string literals may be used to write values of the String primitive type.

For purposes of determining type relationships (section 3.11) and accessing properties (section 4.13), the String primitive type behaves as an object type with the same properties as the global interface type ‘String’.

Some examples:

var s: string; // Explicitly typed

var empty = ""; // Same as empty: string = ""

var abc = 'abc'; // Same as abc: string = "abc"

var c = abc.charAt(2); // Property of String interface

The Symbol primitive type corresponds to the similarly named JavaScript primitive type and represents unique tokens that may be used as keys for object properties.

The symbol keyword references the Symbol primitive type. Symbol values are obtained using the global object ‘Symbol’ which has a number of methods and properties and can be invoked as a function. In particular, the global object ‘Symbol’ defines a number of well-known symbols (2.2.3) that can be used in a manner similar to identifiers. Note that the ‘Symbol’ object is available only in ECMAScript 2015 environments.

For purposes of determining type relationships (section 3.11) and accessing properties (section 4.13), the Symbol primitive type behaves as an object type with the same properties as the global interface type ‘Symbol’.

Some examples:

var secretKey = Symbol();

var obj = {};

obj[secretKey] = "secret message"; // Use symbol as property key

obj[Symbol.toStringTag] = "test"; // Use of well-known symbol

The Void type, referenced by the void keyword, represents the absence of a value and is used as the return type of functions with no return value.

The only possible values for the Void type are null and undefined. The Void type is a subtype of the Any type and a supertype of the Null and Undefined types, but otherwise Void is unrelated to all other types.

NOTE: We might consider disallowing declaring variables of type Void as they serve no useful purpose. However, because Void is permitted as a type argument to a generic type or function it is not feasible to disallow Void properties or parameters.

The Null type corresponds to the similarly named JavaScript primitive type and is the type of the null literal.

The null literal references the one and only value of the Null type. It is not possible to directly reference the Null type itself.

The Null type is a subtype of all types, except the Undefined type. This means that null is considered a valid value for all primitive types, object types, union types, intersection types, and type parameters, including even the Number and Boolean primitive types.

Some examples:

var n: number = null; // Primitives can be null

var x = null; // Same as x: any = null

var e: Null; // Error, can't reference Null type

The Undefined type corresponds to the similarly named JavaScript primitive type and is the type of the undefined literal.

The undefined literal denotes the value given to all uninitialized variables and is the one and only value of the Undefined type. It is not possible to directly reference the Undefined type itself.

The undefined type is a subtype of all types. This means that undefined is considered a valid value for all primitive types, object types, union types, intersection types, and type parameters.

Some examples:

var n: number; // Same as n: number = undefined

var x = undefined; // Same as x: any = undefined

var e: Undefined; // Error, can't reference Undefined type

Enum types are distinct user defined subtypes of the Number primitive type. Enum types are declared using enum declarations (section 9.1) and referenced using type references (section 3.8.2).

Enum types are assignable to the Number primitive type, and vice versa, but different enum types are not assignable to each other.

Specialized signatures (section 3.9.2.4) permit string literals to be used as types in parameter type annotations. String literal types are permitted only in that context and nowhere else.

All string literal types are subtypes of the String primitive type.

TODO: Update to reflect expanded support for string literal types.

Object types are composed from properties, call signatures, construct signatures, and index signatures, collectively called members.

Class and interface type references, array types, tuple types, function types, and constructor types are all classified as object types. Multiple constructs in the TypeScript language create object types, including:

Type references (section 3.8.2) to class and interface types are classified as object types. Type references to generic class and interface types include type arguments that are substituted for the type parameters of the class or interface to produce an actual object type.

Array types represent JavaScript arrays with a common element type. Array types are named type references created from the generic interface type ‘Array’ in the global namespace with the array element type as a type argument. Array type literals (section 3.8.4) provide a shorthand notation for creating such references.

The declaration of the ‘Array’ interface includes a property ’length’ and a numeric index signature for the element type, along with other members:

interface Array<T> {

length: number;

[x: number]: T;

// Other members

}

Array literals (section 4.6) may be used to create values of array types. For example

var a: string[] = ["hello", "world"];

A type is said to be an array-like type if it is assignable (section 3.11.4) to the type any[].

Tuple types represent JavaScript arrays with individually tracked element types. Tuple types are written using tuple type literals (section 3.8.5). A tuple type combines a set of numerically named properties with the members of an array type. Specifically, a tuple type

[ T0, T1, ..., Tn ]

combines the set of properties

{

0: T0;

1: T1;

...

n: Tn;

}

with the members of an array type whose element type is the union type (section 3.4) of the tuple element types.

Array literals (section 4.6) may be used to create values of tuple types. For example:

var t: [number, string] = [3, "three"];

var n = t[0]; // Type of n is number

var s = t[1]; // Type of s is string

var i: number;

var x = t[i]; // Type of x is number | string

Named tuple types can be created by declaring interfaces that derive from Array<T> and introduce numerically named properties. For example:

interface KeyValuePair<K, V> extends Array<K | V> { 0: K; 1: V; }

var x: KeyValuePair<number, string> = [10, "ten"];

A type is said to be a tuple-like type if it has a property with the numeric name ‘0’.

An object type containing one or more call signatures is said to be a function type. Function types may be written using function type literals (section 3.8.8) or by including call signatures in object type literals.

An object type containing one or more construct signatures is said to be a constructor type. Constructor types may be written using constructor type literals (section 3.8.9) or by including construct signatures in object type literals.

Every object type is composed from zero or more of the following kinds of members:

new operator to objects of the given type.Properties are either public, private, or protected and are either required or optional:

Call and construct signatures may be specialized (section 3.9.2.4) by including parameters with string literal types. Specialized signatures are used to express patterns where specific string values for some parameters cause the types of other parameters or the function result to become further specialized.

Union types represent values that may have one of several distinct representations. A value of a union type A | B is a value that is either of type A or type B. Union types are written using union type literals (section 3.8.6).

A union type encompasses an ordered set of constituent types. While it is generally true that A | B is equivalent to B | A, the order of the constituent types may matter when determining the call and construct signatures of the union type.

Union types have the following subtype relationships:

Similarly, union types have the following assignability relationships:

The || and conditional operators (section 4.19.7 and 4.20) may produce values of union types, and array literals (section 4.6) may produce array values that have union types as their element types.

Type guards (section 4.24) may be used to narrow a union type to a more specific type. In particular, type guards are useful for narrowing union type values to a non-union type values.

In the example

var x: string | number;

var test: boolean;

x = "hello"; // Ok

x = 42; // Ok

x = test; // Error, boolean not assignable

x = test ? 5 : "five"; // Ok

x = test ? 0 : false; // Error, number | boolean not assignable

it is possible to assign ‘x’ a value of type string, number, or the union type string | number, but not any other type. To access a value in ‘x’, a type guard can be used to first narrow the type of ‘x’ to either string or number:

var n = typeof x === "string" ? x.length : x; // Type of n is number

For purposes of property access and function calls, the apparent members (section 3.11.1) of a union type are those that are present in every one of its constituent types, with types that are unions of the respective apparent members in the constituent types. The following example illustrates the merging of member types that occurs when union types are created from object types.

interface A {

a: string;

b: number;

}

interface B {

a: number;

b: number;

c: number;

}

var x: A | B;

var a = x.a; // a has type string | number

var b = x.b; // b has type number

var c = x.c; // Error, no property c in union type

Note that ‘x.a’ has a union type because the type of ‘a’ is different in ‘A’ and ‘B’, whereas ‘x.b’ simply has type number because that is the type of ‘b’ in both ‘A’ and ‘B’. Also note that there is no property ‘x.c’ because only ‘B’ has a property ‘c’.

When used as a contextual type (section 4.23), a union type has those members that are present in any of its constituent types, with types that are unions of the respective members in the constituent types. Specifically, a union type used as a contextual type has the apparent members defined in section 3.11.1, except that a particular member need only be present in one or more constituent types instead of all constituent types.

Intersection types represent values that simultaneously have multiple types. A value of an intersection type A & B is a value that is both of type A and type B. Intersection types are written using intersection type literals (section 3.8.7).

An intersection type encompasses an ordered set of constituent types. While it is generally true that A & B is equivalent to B & A, the order of the constituent types may matter when determining the call and construct signatures of the intersection type.

Intersection types have the following subtype relationships:

Similarly, intersection types have the following assignability relationships:

For purposes of property access and function calls, the apparent members (section 3.11.1) of an intersection type are those that are present in one or more of its constituent types, with types that are intersections of the respective apparent members in the constituent types. The following examples illustrate the merging of member types that occurs when intersection types are created from object types.

interface A { a: number }

interface B { b: number }

var ab: A & B = { a: 1, b: 1 };

var a: A = ab; // A & B assignable to A

var b: B = ab; // A & B assignable to B

interface X { p: A }

interface Y { p: B }

var xy: X & Y = { p: ab }; // X & Y has property p of type A & B

type F1 = (a: string, b: string) => void;

type F2 = (a: number, b: number) => void;

var f: F1 & F2 = (a: string | number, b: string | number) => { };

f("hello", "world"); // Ok

f(1, 2); // Ok

f(1, "test"); // Error

The union and intersection type operators can be applied to type parameters. This capability can for example be used to model functions that merge objects:

function extend<T, U>(first: T, second: U): T & U {

// Extend first with properties of second

}

var x = extend({ a: "hello" }, { b: 42 });

var s = x.a;

var n = x.b;

It is possible to create intersection types for which no values other than null or undefined are possible. For example, intersections of primitive types such as string & number fall into this category.

A type parameter represents an actual type that the parameter is bound to in a generic type reference or a generic function call. Type parameters have constraints that establish upper bounds for their actual type arguments.

Since a type parameter represents a multitude of different type arguments, type parameters have certain restrictions compared to other types. In particular, a type parameter cannot be used as a base class or interface.

Class, interface, type alias, and function declarations may optionally include lists of type parameters enclosed in < and > brackets. Type parameters are also permitted in call signatures of object, function, and constructor type literals.

TypeParameters:

< TypeParameterList >

TypeParameterList:

TypeParameter

TypeParameterList , TypeParameter

TypeParameter:

BindingIdentifier Constraintopt

Constraint:

extends Type

Type parameter names must be unique. A compile-time error occurs if two or more type parameters in the same TypeParameterList have the same name.

The scope of a type parameter extends over the entire declaration with which the type parameter list is associated, with the exception of static member declarations in classes.

A type parameter may have an associated type parameter constraint that establishes an upper bound for type arguments. Type parameters may be referenced in type parameter constraints within the same type parameter list, including even constraint declarations that occur to the left of the type parameter.

The base constraint of a type parameter T is defined as follows:

{}.In the example

interface G<T, U extends V, V extends Function> { }

the base constraint of ‘T’ is the empty object type and the base constraint of ‘U’ and ‘V’ is ‘Function’.

For purposes of determining type relationships (section 3.11), type parameters appear to be subtypes of their base constraint. Likewise, in property accesses (section 4.13), new operations (section 4.14), and function calls (section 4.15), type parameters appear to have the members of their base constraint, but no other members.

It is an error for a type parameter to directly or indirectly be a constraint for itself. For example, both of the following declarations are invalid:

interface A<T extends T> { }

interface B<T extends U, U extends T> { }

A type reference (section 3.8.2) to a generic type must include a list of type arguments enclosed in angle brackets and separated by commas. Similarly, a call (section 4.15) to a generic function may explicitly include a type argument list instead of relying on type inference.

TypeArguments:

< TypeArgumentList >

TypeArgumentList:

TypeArgument

TypeArgumentList , TypeArgument

TypeArgument:

Type

Type arguments correspond one-to-one with type parameters of the generic type or function being referenced. A type argument list is required to specify exactly one type argument for each corresponding type parameter, and each type argument for a constrained type parameter is required to satisfy the constraint of that type parameter. A type argument satisfies a type parameter constraint if the type argument is assignable to (section 3.11.4) the constraint type once type arguments are substituted for type parameters.

Given the declaration

interface G<T, U extends Function> { }

a type reference of the form ‘G<A, B>’ places no requirements on ‘A’ but requires ‘B’ to be assignable to ‘Function’.

The process of substituting type arguments for type parameters in a generic type or generic signature is known as instantiating the generic type or signature. Instantiation of a generic type or signature can fail if the supplied type arguments do not satisfy the constraints of their corresponding type parameters.

Every class and interface has a this-type that represents the actual type of instances of the class or interface within the declaration of the class or interface. The this-type is referenced using the keyword this in a type position. Within instance methods and constructors of a class, the type of the expression this (section 4.2) is the this-type of the class.

Classes and interfaces support inheritance and therefore the instance represented by this in a method isn’t necessarily an instance of the containing class—it may in fact be an instance of a derived class or interface. To model this relationship, the this-type of a class or interface is classified as a type parameter. Unlike other type parameters, it is not possible to explicitly pass a type argument for a this-type. Instead, in a type reference to a class or interface type, the type reference itself is implicitly passed as a type argument for the this-type. For example:

class A {

foo() {

return this;

}

}

class B extends A {

bar() {

return this;

}

}

let b: B;

let x = b.foo().bar(); // Fluent pattern works, type of x is B

In the declaration of b above, the type reference B is itself passed as a type argument for B’s this-type. Thus, the referenced type is an instantiation of class B where all occurrences of the type this are replaced with B, and for that reason the foo method of B actually returns B (as opposed to A).

The this-type of a given class or interface type C implicitly has a constraint consisting of a type reference to C with C’s own type parameters passed as type arguments and with that type reference passed as the type argument for the this-type.

Classes, interfaces, enums, and type aliases are named types that are introduced through class declarations (section 8.1), interface declarations (section 7.1), enum declarations (9.1), and type alias declarations (section 3.10). Classes, interfaces, and type aliases may have type parameters and are then called generic types. Conversely, named types without type parameters are called non-generic types.

Interface declarations only introduce named types, whereas class declarations introduce named types and constructor functions that create instances of implementations of those named types. The named types introduced by class and interface declarations have only minor differences (classes can’t declare optional members and interfaces can’t declare private or protected members) and are in most contexts interchangeable. In particular, class declarations with only public members introduce named types that function exactly like those created by interface declarations.

Named types are referenced through type references (section 3.8.2) that specify a type name and, if applicable, the type arguments to be substituted for the type parameters of the named type.

Named types are technically not types—only references to named types are. This distinction is particularly evident with generic types: Generic types are “templates” from which multiple actual types can be created by writing type references that supply type arguments to substitute in place of the generic type’s type parameters. This substitution process is known as instantiating a generic type. Only once a generic type is instantiated does it denote an actual type.

TypeScript has a structural type system, and therefore an instantiation of a generic type is indistinguishable from an equivalent manually written expansion. For example, given the declaration

interface Pair<T1, T2> { first: T1; second: T2; }

the type reference

Pair<string, Entity>

is indistinguishable from the type

{ first: string; second: Entity; }

Types are specified either by referencing their keyword or name, or by writing object type literals, array type literals, tuple type literals, function type literals, constructor type literals, or type queries.

Type:

UnionOrIntersectionOrPrimaryType

FunctionType

ConstructorType

UnionOrIntersectionOrPrimaryType:

UnionType

IntersectionOrPrimaryType

IntersectionOrPrimaryType:

IntersectionType

PrimaryType

PrimaryType:

ParenthesizedType

PredefinedType

TypeReference

ObjectType

ArrayType

TupleType

TypeQuery

ThisType

ParenthesizedType:

( Type )

Parentheses are required around union, intersection, function, or constructor types when they are used as array element types; around union, function, or constructor types in intersection types; and around function or constructor types in union types. For example:

(string | number)[]

((x: string) => string) | ((x: number) => number)

(A | B) & (C | D)

The different forms of type notations are described in the following sections.

The any, number, boolean, string, symbol and void keywords reference the Any type and the Number, Boolean, String, Symbol, and Void primitive types respectively.

PredefinedType:

any

number

boolean

string

symbol

void

The predefined type keywords are reserved and cannot be used as names of user defined types.

A type reference references a named type or type parameter through its name and, in the case of a generic type, supplies a type argument list.

TypeReference:

TypeName [no LineTerminator here] TypeArgumentsopt

TypeName:

IdentifierReference

NamespaceName . IdentifierReference

NamespaceName:

IdentifierReference

NamespaceName . IdentifierReference

A TypeReference consists of a TypeName that a references a named type or type parameter. A reference to a generic type must be followed by a list of TypeArguments (section 3.6.2).

A TypeName is either a single identifier or a sequence of identifiers separated by dots. In a type name, all identifiers but the last one refer to namespaces and the last identifier refers to a named type.

Resolution of a TypeName consisting of a single identifier is described in section 2.4.

Resolution of a TypeName of the form N.X, where N is a NamespaceName and X is an IdentifierReference, proceeds by first resolving the namespace name N. If the resolution of N is successful and the export member set (sections 10.4 and 11.3.4.4) of the resulting namespace contains a named type X, then N.X refers to that member. Otherwise, N.X is undefined.

Resolution of a NamespaceName consisting of a single identifier is described in section 2.4. Identifiers declared in namespace declarations (section 10.1) or import declarations (sections 10.3, 11.3.2, and 11.3.3) may be classified as namespaces.

Resolution of a NamespaceName of the form N.X, where N is a NamespaceName and X is an IdentifierReference, proceeds by first resolving the namespace name N. If the resolution of N is successful and the export member set (sections 10.4 and 11.3.4.4) of the resulting namespace contains an exported namespace member X, then N.X refers to that member. Otherwise, N.X is undefined.

A type reference to a generic type is required to specify exactly one type argument for each type parameter of the referenced generic type, and each type argument must be assignable to (section 3.11.4) the constraint of the corresponding type parameter or otherwise an error occurs. An example:

interface A { a: string; }

interface B extends A { b: string; }

interface C extends B { c: string; }

interface G<T, U extends B> {

x: T;

y: U;

}

var v1: G<A, C>; // Ok

var v2: G<{ a: string }, C>; // Ok, equivalent to G<A, C>

var v3: G<A, A>; // Error, A not valid argument for U

var v4: G<G<A, B>, C>; // Ok

var v5: G<any, any>; // Ok

var v6: G<any>; // Error, wrong number of arguments

var v7: G; // Error, no arguments

A type argument is simply a Type and may itself be a type reference to a generic type, as demonstrated by ‘v4’ in the example above.

As described in section 3.7, a type reference to a generic type G designates a type wherein all occurrences of G’s type parameters have been replaced with the actual type arguments supplied in the type reference. For example, the declaration of ‘v1’ above is equivalent to:

var v1: {

x: { a: string; }

y: { a: string; b: string; c: string };

};

An object type literal defines an object type by specifying the set of members that are statically considered to be present in instances of the type. Object type literals can be given names using interface declarations but are otherwise anonymous.

ObjectType:

{ TypeBodyopt }

TypeBody:

TypeMemberList ;opt

TypeMemberList ,opt

TypeMemberList:

TypeMember

TypeMemberList ; TypeMember

TypeMemberList , TypeMember

TypeMember:

PropertySignature

CallSignature

ConstructSignature

IndexSignature

MethodSignature

The members of an object type literal are specified as a combination of property, call, construct, index, and method signatures. Object type members are described in section 3.9.

An array type literal is written as an element type followed by an open and close square bracket.

ArrayType:

PrimaryType [no LineTerminator here] [ ]

An array type literal references an array type (section 3.3.2) with the given element type. An array type literal is simply shorthand notation for a reference to the generic interface type ‘Array’ in the global namespace with the element type as a type argument.

When union, intersection, function, or constructor types are used as array element types they must be enclosed in parentheses. For example:

(string | number)[]

(() => string))[]

Alternatively, array types can be written using the ‘Array<T>’ notation. For example, the types above are equivalent to

Array<string | number>

Array<() => string>

A tuple type literal is written as a sequence of element types, separated by commas and enclosed in square brackets.

TupleType:

[ TupleElementTypes ]

TupleElementTypes:

TupleElementType

TupleElementTypes , TupleElementType

TupleElementType:

Type

A tuple type literal references a tuple type (section 3.3.3).

A union type literal is written as a sequence of types separated by vertical bars.

UnionType:

UnionOrIntersectionOrPrimaryType | IntersectionOrPrimaryType

A union type literal references a union type (section 3.4).

An intersection type literal is written as a sequence of types separated by ampersands.

IntersectionType:

IntersectionOrPrimaryType & PrimaryType

An intersection type literal references an intersection type (section 3.5).

A function type literal specifies the type parameters, regular parameters, and return type of a call signature.

FunctionType:

TypeParametersopt ( ParameterListopt ) => Type

A function type literal is shorthand for an object type containing a single call signature. Specifically, a function type literal of the form

< T1, T2, ... > ( p1, p2, ... ) => R

is exactly equivalent to the object type literal

{ < T1, T2, ... > ( p1, p2, ... ) : R }

Note that function types with multiple call or construct signatures cannot be written as function type literals but must instead be written as object type literals.

A constructor type literal specifies the type parameters, regular parameters, and return type of a construct signature.

ConstructorType:

new TypeParametersopt ( ParameterListopt ) => Type

A constructor type literal is shorthand for an object type containing a single construct signature. Specifically, a constructor type literal of the form

new < T1, T2, ... > ( p1, p2, ... ) => R

is exactly equivalent to the object type literal

{ new < T1, T2, ... > ( p1, p2, ... ) : R }

Note that constructor types with multiple construct signatures cannot be written as constructor type literals but must instead be written as object type literals.

A type query obtains the type of an expression.

TypeQuery:

typeof TypeQueryExpression

TypeQueryExpression:

IdentifierReference

TypeQueryExpression . IdentifierName

A type query consists of the keyword typeof followed by an expression. The expression is restricted to a single identifier or a sequence of identifiers separated by periods. The expression is processed as an identifier expression (section 4.3) or property access expression (section 4.13), the widened type (section 3.12) of which becomes the result. Similar to other static typing constructs, type queries are erased from the generated JavaScript code and add no run-time overhead.

Type queries are useful for capturing anonymous types that are generated by various constructs such as object literals, function declarations, and namespace declarations. For example:

var a = { x: 10, y: 20 };

var b: typeof a;

Above, ‘b’ is given the same type as ‘a’, namely { x: number; y: number; }.

If a declaration includes a type annotation that references the entity being declared through a circular path of type queries or type references containing type queries, the resulting type is the Any type. For example, all of the following variables are given the type Any:

var c: typeof c;

var d: typeof e;

var e: typeof d;

var f: Array<typeof f>;

However, if a circular path of type queries includes at least one ObjectType, FunctionType or ConstructorType, the construct denotes a recursive type:

var g: { x: typeof g; };

var h: () => typeof h;

Here, ‘g’ and ‘g.x’ have the same recursive type, and likewise ‘h’ and ‘h()’ have the same recursive type.

The this keyword is used to reference the this-type (section 3.6.3) of a class or interface.

ThisType:

this

The meaning of a ThisType depends on the closest enclosing FunctionDeclaration, FunctionExpression, PropertyDefinition, ClassElement, or TypeMember, known as the root declaration of the ThisType, as follows:

Note that in order to avoid ambiguities it is not possible to reference the this-type of a class or interface in a nested object type literal. In the example

interface ListItem {

getHead(): this;

getTail(): this;

getHeadAndTail(): { head: this, tail: this }; // Error

}

the this references on the last line are in error because their root declarations are not members of a class or interface. The recommended way to reference the this-type of an outer class or interface in an object type literal is to declare an intermediate generic type and pass this as a type argument. For example:

type HeadAndTail<T> = { head: T, tail: T };

interface ListItem {

getHead(): this;

getTail(): this;

getHeadAndTail(): HeadAndTail<this>;

}

The members of an object type literal (section 3.8.3) are specified as a combination of property, call, construct, index, and method signatures.

A property signature declares the name and type of a property member.

PropertySignature:

PropertyName ?opt TypeAnnotationopt

TypeAnnotation:

: Type

The PropertyName (2.2.2) of a property signature must be unique within its containing type, and must denote a well-known symbol if it is a computed property name (2.2.3). If the property name is followed by a question mark, the property is optional. Otherwise, the property is required.

If a property signature omits a TypeAnnotation, the Any type is assumed.

A call signature defines the type parameters, parameter list, and return type associated with applying a call operation (section 4.15) to an instance of the containing type. A type may overload call operations by defining multiple different call signatures.

CallSignature:

TypeParametersopt ( ParameterListopt ) TypeAnnotationopt

A call signature that includes TypeParameters (section 3.6.1) is called a generic call signature. Conversely, a call signature with no TypeParameters is called a non-generic call signature.

As well as being members of object type literals, call signatures occur in method signatures (section 3.9.5), function expressions (section 4.10), and function declarations (section 6.1).

An object type containing call signatures is said to be a function type.

Type parameters (section 3.6.1) in call signatures provide a mechanism for expressing the relationships of parameter and return types in call operations. For example, a signature might introduce a type parameter and use it as both a parameter type and a return type, in effect describing a function that returns a value of the same type as its argument.

Type parameters may be referenced in parameter types and return type annotations, but not in type parameter constraints, of the call signature in which they are introduced.

Type arguments (section 3.6.2) for call signature type parameters may be explicitly specified in a call operation or may, when possible, be inferred (section 4.15.2) from the types of the regular arguments in the call. An instantiation of a generic call signature for a particular set of type arguments is the call signature formed by replacing each type parameter with its corresponding type argument.

Some examples of call signatures with type parameters follow below.

A function taking an argument of any type, returning a value of that same type:

<T>(x: T): T

A function taking two values of the same type, returning an array of that type:

<T>(x: T, y: T): T[]

A function taking two arguments of different types, returning an object with properties ‘x’ and ‘y’ of those types:

<T, U>(x: T, y: U): { x: T; y: U; }

A function taking an array of one type and a function argument, returning an array of another type, where the function argument takes a value of the first array element type and returns a value of the second array element type:

<T, U>(a: T[], f: (x: T) => U): U[]

A signature’s parameter list consists of zero or more required parameters, followed by zero or more optional parameters, finally followed by an optional rest parameter.

ParameterList:

RequiredParameterList

OptionalParameterList

RestParameter

RequiredParameterList , OptionalParameterList